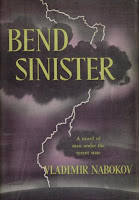

Bend Sinister (1947) may not be the most acclaimed or well known of Nabokov’s novels, but it holds a special place on my bookshelf – when I am not lending it to friends and colleagues as, “a good introduction.” But Bend Sinister is more than a stepping off point; in its own right, it is a perfect microcosm of Nabokov’s art and the possibilities of fiction.

Bend Sinister (1947) may not be the most acclaimed or well known of Nabokov’s novels, but it holds a special place on my bookshelf – when I am not lending it to friends and colleagues as, “a good introduction.” But Bend Sinister is more than a stepping off point; in its own right, it is a perfect microcosm of Nabokov’s art and the possibilities of fiction.Set in an unnamed European country which has recently allowed a new dictator into power, Bend Sinister, written on the heels of the darkest half-century in human history, is both of its time and timeless. The protagonist, Adam Krug, is a well-known intellectual naturally opposed to the new regime’s policy of “Ekwilism”, but his crisis is a personal one. Krug has just lost his wife when the novel opens, and by its close, he will lose everything. The cruellest blow is the clerical error which sends his son – taken hostage to coerce Krug into endorsing Ekwilism – to The Institute for Abnormal Boys, where he meets an “accident”. At this point, the narrator steps forward and reveals himself as Nabokov the novelist, and through, “an inclined beam of pale light,” he grants Krug the madness to free himself of the twin tyrannies of grief and despotism.

It is by design that a reader chuckles their way through what is, on one level, a bleak tragedy – and that the greatest injustice (the death of Krug’s son, David) occurs offstage. The novel ends suddenly after Nabokov steps forward and confirms that it is all made up. After so much genre-blending, the very boundaries of fiction have faded and it is only natural for a reader to feel uneasy. This delayed unease is a classic Nabokovian ploy. We do not feel for Krug, his son or his doomed colleagues until it is too late. But, with the curtain of fiction dropped, the reader is invited to assume the role of Adam Krug, to play protagonist in this world, but also to recognize the tyrannies at work in one’s own existence.

While I fall in love with new books and new authors every year, Bend Sinister was the first to open my eyes to the possibilities of fiction, and for that reason, it will always have a seat reserved at my last supper.

No comments:

Post a Comment